I continue to explore data about my physical activity in 2013 (see part 1). We moved from an apartment (on the third floor of a building) to a house (with two floors) on July 1st, 2013. I was wondering if the change would have an impact on the number of floors I climbed: I now have to climb to reach bedrooms and go down to go in the living room. A standard house.

Two things before diving into data … First I sometimes used to climb the stairs to the 3rd floor in my building (and I worked all the time at the same floor at the office). Then only the Fitbit One is collecting the number of floors you climb, not the Flex (you can enter them in the web interface but I don’t). So I don’t value the data after I lost my Fitbit One (Sep. 16). I don’t really know how the One determines the number of stairs I climb but I felt it was fairly accurate. For instance when I climbed 3 stairs in my building, the One always indicated +3 stairs on its counter.

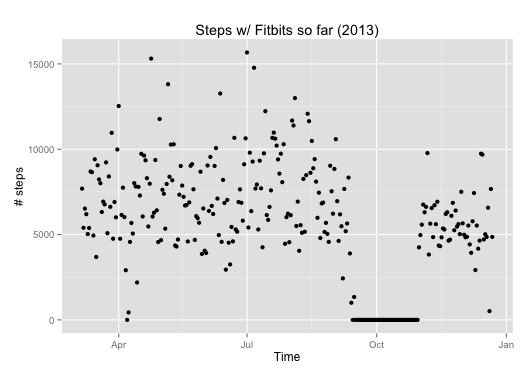

So now the data. I updated the R scripts and here is what I get for the number of floors.

On average I did not climb a lot of stairs. In general it is below 20. And if I compare the data before and after the move there is indeed a significant difference (p=2.49e-06)! But I was climbing more floors when I was in my apartment than when I was/am in a house (respective means of 12.59 and 7.37 floors)!

On average I did not climb a lot of stairs. In general it is below 20. And if I compare the data before and after the move there is indeed a significant difference (p=2.49e-06)! But I was climbing more floors when I was in my apartment than when I was/am in a house (respective means of 12.59 and 7.37 floors)!

There are a few outliers, days when I climbed relatively more than others. Going back to my agenda, it corresponded to:

- one day I took holidays just after the move in order to arrange things at home (strangely the days of the move doesn’t correspond to more of that activity);

- one day when I came back from a business trip (I had to walk a lot to/in/from airports);

- two days with no particular event.

The lessons I take are that you don’t necessarily need stairs in the area where you live to actually climb more floors (in my case it appears to be the opposite). And I don’t necessarily need to have a specific activity to climb more floors, hence it’s a question of willingness more than anything else.

Next post: how much sleep did I get in 2013!