Statbel, the Belgian governmental organisation for data and statistics, just released mortality data for 2014 (press release in French, dataset). The headline of their press release was that, for the first time, tumors were the first cause of death for Belgian men. Diseases of the circulatory system remains the main cause of death in Belgium, for women and for both sex together.

While the death of someone is a bad news in itself, I’m more interested here in the evolution of death causes. I’m interested in the evolution of causes of death because it might be a consequence of the evolution of the Belgian society and, as a proxy, of any (most) developed, occidental countries.

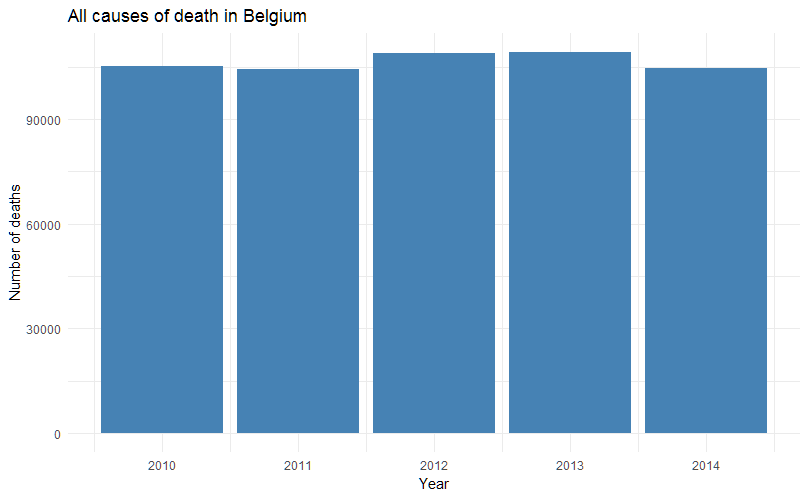

If you look at the data, the number of Belgians dying is stable and natural death is still the main cause (and also stable, around 93%). Note that if we look at data before 2010, it seems that mortality is slightly increasing since around 2005.

If the total number of deaths seems stable, the press release seemed to indicate that tumors (cancers) are on the rise, especially in men. The breakdown in categories is made following the international classification ICD-10 and, because the names of the different chapters are quite long for graphs, I will use the corresponding chapter numbers instead. Here is the key:

| Chapter | Header |

|---|---|

| I | Certain infectious and parasitic diseases (A00-B99) |

| II | Neoplasms (C00-D48) |

| III | Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism (D50-D89) |

| IV | Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases (E00-E90) |

| V | Mental and behavioural disorders (F00-F99) |

| VI | Diseases of the nervous system (G00-G99) |

| VII | Diseases of the eye and adnexa (H00-H59) |

| VIII | Diseases of the ear and mastoid process (H60-H95) |

| IX | Diseases of the circulatory system (I00-I99) |

| X | Diseases of the respiratory system (J00-J99) |

| XI | Diseases of the digestive system (K00-K93) |

| XII | Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (L00-L99) |

| XIII | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (M00-M99) |

| XIV | Diseases of the genitourinary system (N00-N99) |

| XV | Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium (O00-O99) |

| XVI | Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period (P00-P96) |

| XVII | Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities (Q00-Q99) |

| XVIII | Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (R00-R99) |

| XX | External causes of morbidity and mortality (V01-Y98) |

One thing to notice is that, for chapter IV, Statbel only counts categories E00 to E88 while the WHO includes 2 more, from category E00 to E90 ; I would assume here that it has no important impact. Also note that, below, R ordered the chapters in a strange way – I’ll see how to fix that.

Excluding natural causes, we see that indeed, diseases of the circulatory system (chapter IX) are still the first cause of death, followed by neoplasms (chapter II) and diseases of the respiratory system (chapter X). If we compare the relative ratio of all these causes (second graph below), we also find the same conclusion – but the relative decline in deaths due to diseases of the circulatory system is better shown. And we can see that neoplasms take back approximately the same relative percentage of death, in 2014 (although they returned to the absolute number of deaths of 2012, approximately).

The available data set doesn’t go into more details than numbers by ICD-10 chapters. Therefore we cannot tell from that what kind of neoplasm is the most prevalent or what kind of infectious disease is the most present in Belgium, for instance. The press release however mentions that respiratory, colorectal and breast cancers are the top three killers and that flu was not very present in 2014.

As the cancer occurrence is increasing with age, and as the Belgian population is aging, one of the explanation for a high number of deaths due to neoplasms can be age ; however we don’t see a dramatic increase of neoplasms (fortunately!). Another potential factor is the impact of screening for cancers. Due to a very intelligent political split (sarcasm!), prevention (and therefore screening) is not a federal duty. Therefore regions started different screening programs, at different times, with different results. Screening data and their results are therefore difficult to obtain. The Belgian Cancer Registry doesn’t publish data on screening in oncology – although its latest report (revised version of April 2016) very often mentions screening as a main factor for change in the number of cases diagnosed. In its 2016 report (PDF), the Flemish Center for the Detection of Cancer (Centrum voor kankeropsporing) indicates that they increased the number of women screened for breast cancer by more than 8% between 2011 and 2015 (especially in 2015), with a quality of test between 90% and 95%. They also showed an increase in cancer diagnostics (without linking it directly to the increase in screening).

This is by no means an exhaustive review of the data. There are other potentially interesting things to look at: the geographical disparities between the three regions, the gender ratio evolution (as some of these diseases are known or by definition affecting more one sex than the other), etc.

It would also be interesting to follow these trends as some changes occurred recently in the Belgian curative landscape. New drugs in cancer immunotherapy were recently authorised and reimbursed, for melanoma, lung – and other indications will follow. These costs have a price (less than what is in the press, however, I may come back on this in a future post) but they delay death (unfortunately they don’t avoid it). However, for some of them, in some indications, their administration and reimbursement is sometimes also linked with screening, testing and prior treatment failure ; that might decrease their impact on overall mortality. New drugs for Hepatitis C also arrived in 2015 and 2016 and the Belgian health minister decided to reimburse these drugs for patients in their early stage 2 of the disease. Studies showed that treating at this stage may prevent hepatitis C from progressing to later stages and, in some cases, studies showed patients cured from the disease. This is an opportunity to see a decline in mortality due to this infectious disease (although it is already quite low – compared to other diseases).